Cambridge Team Visits UCL to Begin SHeM Sample-Transfer Tests

Yesterday we were pleased to welcome Dr Jack Kelsall and PhD student Ke Wang from the University of Cambridge for a collaborative visit to our UHV-STM laboratory.

Their trip forms part of a new collaboration with the Surface Physics Group at Cambridge and with Professor Paul Dastoor from the University of Newcastle, Australia. Our role is the preparation of atomically clean and flat hydrogen-terminated silicon (001) surfaces, which will then be imaged with the scanning helium microscope (SHeM) at Cambridge. The collaboration was initiated by Paul, who is currently on sabbatical at Cambridge, together with David Ward and Holly Hedgeland.

The scanning helium microscope (SHeM) operates in a way that is conceptually similar to a scanning electron microscope (SEM), but instead of electrons it uses a beam of neutral helium atoms. Because the atoms are uncharged, light, and chemically inert, the technique can image insulating or fragile surfaces that are inaccessible to SEM and without the risk of beam-induced damage. The helium beam is produced by expanding gas from a high-pressure source at room temperature, giving a beam energy of around 50 meV and a wavelength close to 1 Å. Current limitations in the atom optics and detector restrict the imaging resolution to about 0.5 μm, but nanometre-scale imaging is anticipated with future instrumentation developments.

The current project aims to test whether the SHeM is sensitive to hydrogen atoms chemically bound to atomically flat silicon surfaces. While hydrogen termination of silicon wafers can be achieved through wet-chemical treatments, the highest-quality hydrogen-terminated Si(001) surfaces are produced by exposing atomically clean Si(001) to a beam of hydrogen atoms in an ultrahigh-vacuum chamber. Our group has long experience preparing and characterising such surfaces, but transporting them from UCL to Cambridge while retaining their cleanliness presents a challenge. To address this, we have developed a compact “vacuum suitcase” — a small, portable vacuum chamber with its own pump that can be attached both to our UHV-STM system in London and to the SHeM system in Cambridge and enabling us to keep the sample surface clean at the atomic-scale for its journey from London to Cambridge.

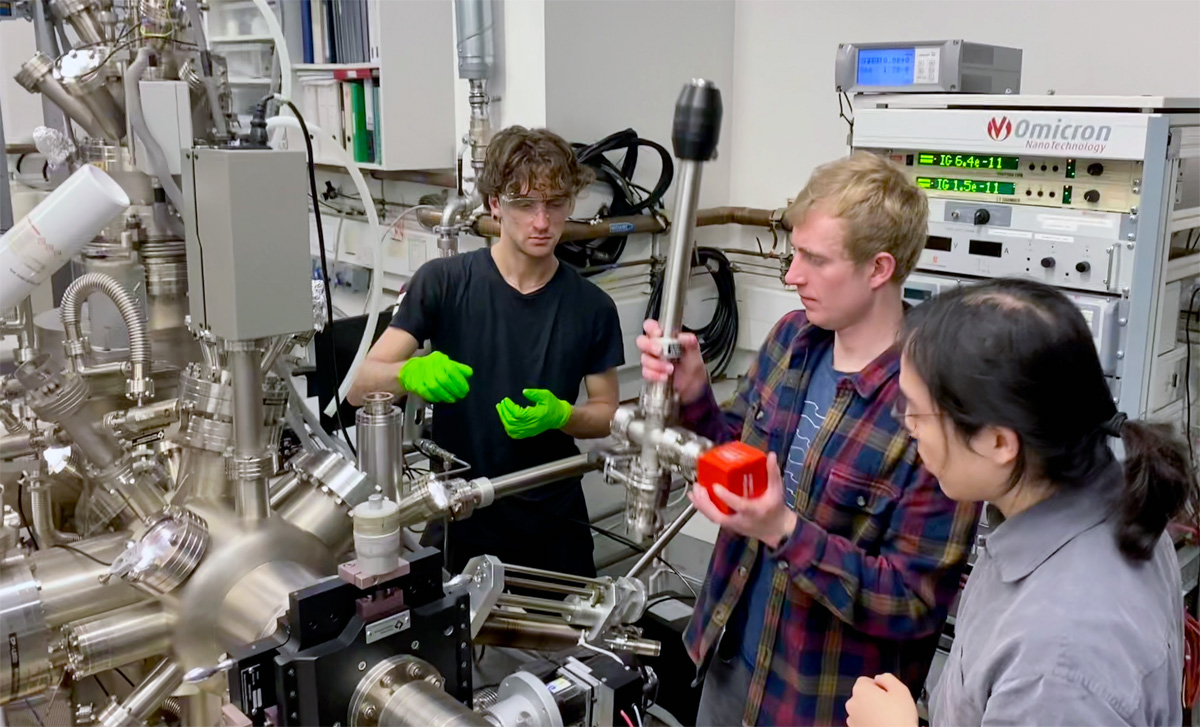

Yesterday’s visit marked our first full test of this suitcase for sample transfers to the UHV-STM. The photo above shows Byron assisting Jack and Ke as they mounted it onto the entry lock of our STM system. The test was largely successful and demonstrated that the concept is sound, although it also revealed a small design issue in the sample-reception stage. This will now be redesigned and fabricated in the Cambridge workshop before we attempt further transfers and, hopefully, deliver the first samples for SHeM imaging early in the new year.

This collaboration also has a personal resonance for me. My connection with Paul goes back thirty years, to when he was a newly appointed lecturer at the University of Newcastle in Australia and taught me as an undergraduate. As anyone who knows Paul can attest, his enthusiasm for science is unmissable and undoubtedly helped strengthen my interest in a career in research physics. Our paths crossed again when I returned to Newcastle as an Australian Research Council Postdoctoral Fellow after completing my PhD at UNSW. The links run deeper still: Holly was a postdoc in our group, and Ke completed his undergraduate degree at UCL and took my second-year Quantum Physics course. It has been great fun to see so many connections come together in this collaboration, and we’re looking forward to the first SHeM measurements on hydrogen-terminated silicon prepared here at UCL.